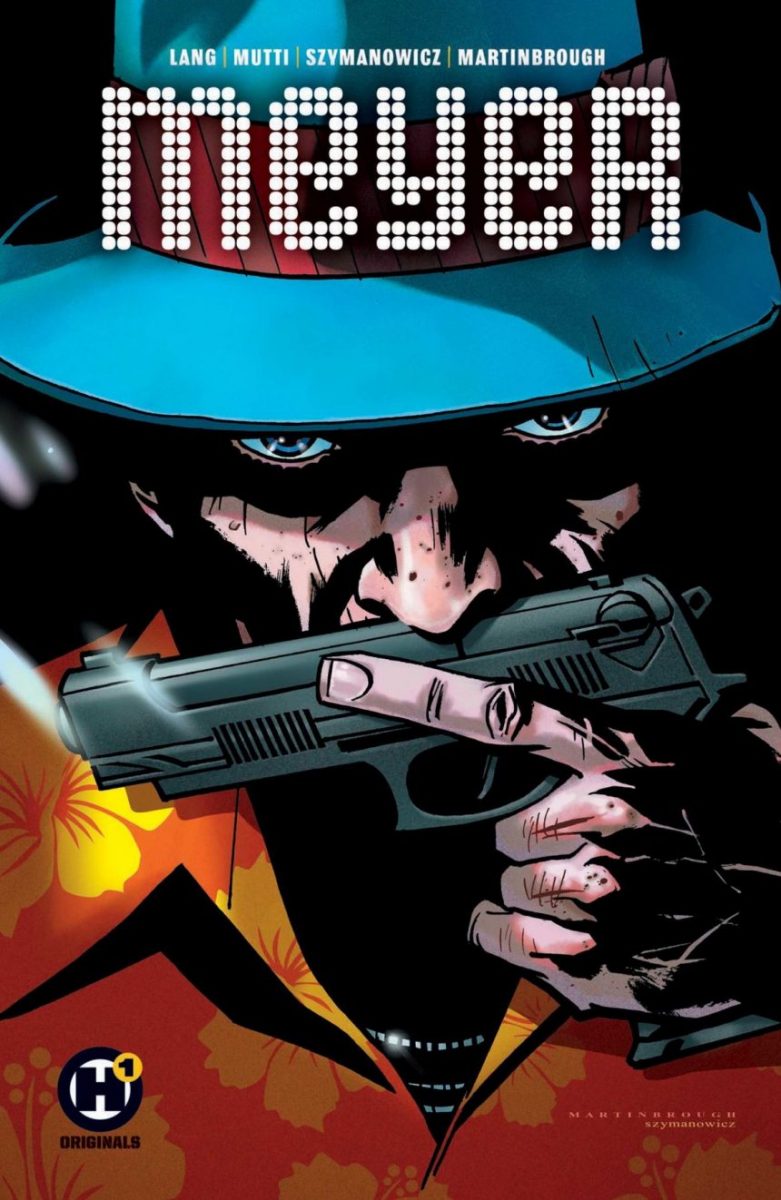

Who was Meyer Lansky? What was his impact on the underworld and beyond? That is not the question at the heart of “Meyer,” the newest graphic novel from Humanoids’ H1 imprint. Instead, we are treated to an examination of the growing old in a field that does not lend itself to longevity and the fictional final job of the mobster’s life. Originally announced as a 5-issue series under Humanoids’ H1 imprint, “Meyer” is now coming out as a graphic novel. In preparation for its release on September 25th, we chatted with writer Jonathan Lang about Meyer Lansky, 1980s Miami Beach, and legacy.

To start us off, this is your first graphic novel, though not your first foray into comics. What about the format influenced the pacing and the contents of “Meyer,” if at all?

Jonathan Lang: Even though this is my first proper graphic novel, I would say all of my projects are written linearly as opposed to more of a serialized approach. I think that is a really specific kind of storytelling and it is a true art to both have an issue that is self-contained and part of a larger arc. Because of my film background, I tend to think of stories like stand-alone movies, sequel free, and if you were to pick up an issue in the middle of the run, it would be confusing. I try to write where a detail in issue one may not have an echo until the last issue.

For this project, I think the real difference is I had a very clear view of the ending. I knew from the outset where these characters had to arrive. It changed, of course, because of a fantastic conversation with the AMAZING editorial team (Fabrice Sapolsky and Amanda Lucido). I knew where I wanted to take the duo. Not knowing the ending has worked for me in some ways, as it allowed me to wander and explore a bit, but plotting in comics is so important. In some ways, it is the job. It is also something I really have to work hard at accomplishing.

The other approach was to try starting a scene at the emotional climax. For example, on “Feeding Ground,” we really tried the slow burn, and for the setting that made both logical and emotional sense. For “Meyer,” I tried to dunk the reader’s head into a bucket of cold water. I wanted to wake them up. That feels right when you are dealing with mobsters.

You do a fantastic job of weaving in the important moments in Meyer’s life throughout “Meyer,” allowing those unfamiliar with the man to learn about who he was. Did you find yourself drawing more and more or less and less from his past as you scripted the story? Or, put another way, was the semi-biographical nature of the work a help in the writing process?

JL: I absolutely drew on his life for scripting. It was the springboard. I have no idea if he works this way, but I have always imagined Ed Brubaker’s process as writing an incredible paragraph of prose, and then beating out the panel work visually to both support and contradict his language. This method was my approach. Meyer would monologue his life in my head, and I would jot it down as quickly as possible. I then would have an image appear, or an action sequence that would support the monologue. I just let these images appear.